Trailokya Jena

Every disaster in modern times, whether natural or man made, gets identified with photographs to define it for posterity. The naked girl child fleeing from napalm bombing in Vietnam 1972, the terrified tailor pleading with folded hands in riot torn Gujarat 2002, the drowned Syrian refugee kid lying face down on unidentified beach 2015 are some of the defining moments of terrible man made crisis of our time. The current pandemic is far from over but I am willing to bet my last rupee on what is going to be the defining photograph of it for future historians. It is the lead photo of this blog, Rotis on the Railway Tracks. Not only this has been a tragedy of epic proportion, it serves as the defining paradox of the plight of the unfortunates, the inevitable tragic end of the homebound group is the denouement ordained by the rules of classical Greek tragedy. Can it be more ironic than this situation where the migrants originally suffer as trains stop running to take them home but then meet nemesis on the very tracks which was closed to them for home return. The wastage of those rotis flung around compete with the wastage of human lives as the draconian lockdown makes rotis more valuable than human life.

The incident took place after 44 days of lockdown which can not be said to be a period too short to sort things out. With people confined to homes and news papers practically extinct, one had no option but to follow the incident on the electronics media whose versions varied widely. If you google it today, you’ll not get the correct number of migrants killed as each agency’s numbers vary with the others. I’ve, therefore, gone to BBC for its report on the incident as I’d trust it more than any of our channels no matter how much I blame the Brits for most of our woes. The news as quoted:

“Railway officials say the workers walked on the road towards Aurangabad, and later on railway tracks leading to Aurangabad.

After walking for 22 miles (36km), they were exhausted and decided to rest.According to local reports, the workers assumed that trains would not be running because of the lockdown, and therefore slept on the tracks. Images on social media show pieces of roti (Indian bread) strewn near the tracks.”

Sekhar Gupta, the erstwhile editor of Indian Express and now of the e-news platform The Print, is perhaps the last of the classical newsmen of India coming down from Sham Lal, Kuldeep Nair, Girilal Jain, S Nihal Singh to name a few. In his May 23 edition of National Interest (PM, CM, DM) he has explained how the Prime Minister, Cheif Ministers and District Magistrates have seized the three engines of India’s governance and where, between them, they have failed the country in the handling of this pandemic crisis. It has made my task easy as the basic problems in our governance structure can be accessed by googling Shekhar’s video. If we have to understand the catastrophic situation of the migrants we may to have to analyse the structure more directly. After promulgations of the Epidemics Act and the Disaster Management Act, everything hinges on the Centre. The quarrel over cooperative federalism is a red herring for both Centre and State politicians to hide incompetence. Serious search for accountability has to go through critical examination of the roles of these three levels ( to be fair the DM level has to be expanded to the wider span from Delhi to the districts).

The PM takes credit for bold and surprise actions. Two of his past such actions, namely demonetisation and GST implementation, that affected life across the country have been much discussed by both supporters and opponents. Most citizens trusted the PM on these decisions in spite of their terrible implementations and stoically endured prolonged hardship. It doesn’t take great insight or knowledge to understand that such far reaching decisions were thrust upon without adequate preparation on part of the implementation machinery. However, on both occasions the system never acknowledged the flaws, did nothing to identify the administrative unpreparedness and didn’t call for accountability. The bureaucrats responsible for public hardship got rather rewarded which has led to the mishandling of this more serious pandemic response. The institutional memory that the government possesses can never be doubted. Number of crises in the past must have got automatically flagged to warn the ministries that any crisis in the city automatically triggers its migrants to rush back home. In recent memory you’ve the Bombay riots/bomb blast of 1992/3, Surat Plague of 1994, Gujarat riots of 2002, and many periodic xenophobic persecution of North Indians in Mumbai and the violence against north easterners in Bengaluru. At the first sign of trouble and loss of work people move towards their native places. No one in the ministries should have missed these when total lockdown was planned which had to affect migrants in many ways and worst of all the cutting out of their escape route by closure of all transport. Someone should have, or must have, flagged it for action. And if not those failing here must be identified and taken to task. Even if States were to manage the migrants, mechanism and fall backs should have been decided. In any case the Centre, given the powers assumed by it under the Epidemics and Disaster Management Acts should have taken direct control of the situation. Even a bold announcement or clear direction to the States could have assured the migrants a great deal. Who are we going to hold accountable here?

Sekhar Gupta in his Cut the Clutter episode 472 aired last week has put interesting perspective on the migrant situation which, he says, has now dominating the stories worldwide thereby down grading India’s good numbers on the fight against the pandemic. That has hugely dented the possible claim of Modi to global heights which definitely hurts him. Sekhar compares the situation to a critical point in cricket matches where you drop a crucial catch which could cost you the match. Good example in the context of a statistically oriented State action for a cricket crazy nation, but I like to take it further. Modi not only dropped the catch here but tipped the ball over the ropes for a six! To compound matters, in marathon announcements of State action over five days of high trp drama, he seems to have done nothing to quickly redeem the situation by not taking the migrant bull by the horn. Imagine the few hours of chaos in front of railway stations. The accountability here is telling and it would take its toll inspite of a pathetic, clueless, moribund and politically challenged opposition. The PM and his office must bear the accountability for the bureaucratic maze and red tape over the confusion of migrants transport to their home states that washed down the drain the health gains from 50 days of draconian lockdown in a few hours of chaotic crowding. Imagine if the migrants could have been transported home in the initial days of lockdown 1.0, would we be having the current spike all over the country for most of them have lost immunity and have got infected.

The stories of the CMs play on predictable lines. The basic response unites all of them in a desperate statistical game of one upmanship where each plays like batsmen of dysfunctional teams to retain places by keeping their averages intact irrespective of the team needs. The desperate race to keep good statistics resulted in the receiving States trying to push the migrants out while the sending States created all sorts of barriers to get them back. While some managed it better, some others constantly muddied the pitch by politicising every aspect of the migrant situation. In any case they all have easy escape routes citing the Centre’s overall control under the health and disaster laws. While some like Navin Patnaik was proactive in sorting out arrangements with other CMs of location States and preparing infrastructure to absorb migrants others like Mamata Banerjee was erecting hurdles to take responsibility. Having reaped the fruits of migrant labourers all these times, CMs in both sending and receiving States abandoned them when they are most vulnerable.

That brings us to the DMs which must be read with a wider connotation to include the key players of the bureaucratic hierarchy. Policy decisions in the government both at the Centre and the States are taken at the highest levels under political executives but then entire execution has to pass through the eye of the needle that is the District Magistrates. Nothing is possible in governance terms in the districts of India which is not controlled and blessed by the DM. An office which was originally created by Cornwallis of East India Company primarily for land revenue collection in 1792 Bengal, was extended to other parts of Company’s India by Wellesley in 1798 formally creating the office to head each districts for administering in every respect from revenue collection to law and order to dispensation of justice extending even to protection of its territorial integrity. That’s like putting one executive in control of both North and South Block in Delhi! There is an excellent account of this institution in Philip Mason (an ex ICS Officer in 1930s and 40s in India) 1953 book The Men Who Ruled India, available now in Rupa Publications 1985. If you read Mason’s detailed account you’ll be surprised to find how little this institution has changed in 222 years. While State functions have changed enormously over centuries the office of the DM still controls everything that affect the lives of the people in the districts save justice and defence functions. The sheer numbers of ever expanding state welfare programmes in the country that should drown an entire system still get administered by this single office to all practical purposes. The DM continues to act as the legate of Mughal or British days being accountable to the Emperor or his direct legatee. In his introduction to the book Mason reveals ‘…..how a handful of his countrymen mastered and ruled so many millions ……that so often the District Officer really was at heart what the villagers called him in their petitions, the father and mother of his people’. Many villages have been turned to cities, the British rulers have log left putting the native politicians in charge, but DM still continues to be mai-baap of the people! He or she still continues to separate the ruler from the ruled and the rulers find it so convenient to shield themselves from the ruled. To be fair to the DMs it is too much burden for one office to handle butIndian Administrative Service(IAS) whose most prominent identity is the office of DM is unwilling to dilute its stranglehold over India by giving up or sharing parts of the burden. Our politicians, who have conveniently substituted themselves to the British colonialists, too find the arrangements to their liking as a single window control of the citizens. The IAS as an institution has a permanent stake in continuing the status quo and has mastered the art of managing politicians over the years mainly through the office of the DM right from the breeding grounds of both sets of power groups. The IAS has perfected the art of dynamic lethargy where everybody looks terribly busy for doing very little. The hardest thing in any executive structure is to do nothing and the IAS does it very well. Moreover they are very clever in usurping authority and power at the slightest opportunity and this current lockdown situation has allowed them to unleash a coercive State tilting the balance between individual and the State entirely in favour of the State.

After reading Mason’s book and after going through a great deal of India Office records in the British Library in course of my research last year, I came to realise how the ICS/IAS system teaches its members from inception about human hierarchy and how Officers get increasingly convinced as their career progresses that the majority at the bottom of the pyramid are dispensable. Of course there are a few who are different but as a matter of rule not many from them go very far. We have to look at bureaucratic accountability in these contexts and examine where things go wrong and how. It is the duty of these professionals to bring up institutional memory and flag possible scenarios to the political decision makers. The inevitable fall out of the migrants’ situation, therefore, should have been brought on the table and measures to anticipate their hardship and its mitigation worked out. As we have discussed the recurring examples of lack of problem anticipation, bad implementation and pathetic mitigation measures of other mass measures under Modi government, it would be fair to lay the blame on the bureaucratic machinery. They have been emboldened because their accountability was not questioned for past failures and some key decision makers even got rewarded instead. That not only led to their dynamic lethargy controlling key impacts of the lockdown but continued through no or wrong mitigation measures. Then again it should be established as to what led to the convoluted response to the migrants travel cost once it was decided that they would be ferried by trains. The long standing procedure of cost sharing between the Centre and States is archaic, a relic from the Planning Commission approach to projects. While there could have been some rationale behind token sharing by States of the cost at normal times it was a monumental blunder to go for the moronic 85-15 cost sharing in this desperate situation. It does not stand to common sense when the States are entirely dependent on Central economic assistance and it was going to be only a financial adjustment between the parties. Who advised such a non sensical arrangement and who approved it? There are many small and big failures on part of the bureaucracy and the only way to fix responsibility is to conduct a thorough impartial inquiry into the entire mechanism of the lockdown in appropriate time so as to rid India of these recurring blunders. Civil society must make determined effort to demand such an enquiry as neither the opposition nor the media has made any move on this.

Now to future measures to safeguard the interest of the migrant labourers. Though most migrants vow not to return, these are emotional response under stress. There is no way 60% of rural population can make a living on 15% of our GDP. Economic migration is inevitable and there would be permanent push factors in the villages to send people out. Besides, the urban based industrial and service sectors would always need workers and create its pull factors. The governments at the Centre and the States may make tall claims about self sufficiency but that would not work on a strict rural urban divide. We have to re-contextualise the entire migration issue in a rational economic and legal framework where both the sending and receiving States have to create social and legal infrastructure to manage seamless movements of labour on market principle. Unfortunately in situations like what we have today political authorities generally overreact to take highly populist and incorrect stance to play upto public emotion for selfish electoral gains. We already have responses from some States who want to issue permission for movement of labour out of their territory. This is very ill conceived and is entirely likely to distort the lives of families. The most vulnerable are the circular migrants who move out of villages and return according to seasonal activities at both ends. Their migration decision is determined by family structure and economic situation as the family decides who and how many should migrate to increase overall household income. As migration flow of this vulnerable group are governed by decisions at the family rather than individual level top down government interference would be very counterproductive. It would rather be preferable to both record and counsel these movements at the village Panchayat levels as conceived, but not effectively managed, in Odisha.

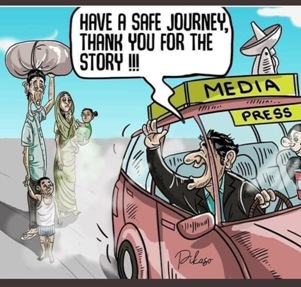

The single most challenge of inter state migration is the problem of acquiring effective identity. It is now very difficult to find a civic identity by a migrant labourer at the destination point severely curtailing his/her bargaining power. The next corollary problem is not finding proper housing and shelter which make it difficult for them to find social protection and to get their entitlements as citizens. The recent proposals for portability of identity to receive core entitlements like food and social security will help if carried out effectively. But issues like health and children’s education can not be tackled with that. Then there are issues relating legal protection which the current Inter State Migrant Act is unable to ensure. Besides the current move towards labour reforms is getting mired in the opportunistic fight between the leftist-socialist liberals and the neo cons right which threatens to sideline the migrants rights altogether. The labour vested interests who have been enjoying cosy protection under the existing laws would not be interested in bringing in the vast unorganised body of migrants into the legal equation. I can clearly foresee the entire migrant labourers’ legal and social protection issues would be hijacked by leftists, socialists, and the so called liberals to fit their agenda in opposing the labour reform moves where as the migrants are not at all covered under any existing significant labour laws. Our fractured polity will trudge on purposelessly. Only an impartial inquiry by credible personalities from civil society can unearth the mistakes committed and can identify the culprits. I wouldn’t trust the three established estates of the State or the Fourth Estate as each one of them has become incompetent, callous or compromised.

– Concluded –

(Trialokya Jena is a former principal chief commissioner of Income Tax)