By Trailokya Jena

Just how well we know China? Are we well informed about its history, geography, culture and politics? It’s all the more important to ask these questions now as China competes with corona virus, ironically one of its many exports, to occupy larger space in our mind. Our Euro centric study of history, a legacy from colonial days, has deprived us of vital knowledge and information on two countries, US and China , that matter most globally for quite sometime while Europe slipped into a corner of history. Hence all those rote of Italian and German Unifications and the World Wars hardly suffice to survive in the 21st century world. Our academic curricula do not reflect the changed reality. US history as I understand has come to undergraduate courses only recently. Chinese study is limited to very few elite institutions where experts on China constitute a closed club that zealously guards its knowledge and exposure against popular studies. To compound matters, study of China is a difficult pursuit as the Communist administration have been wiping their past clean so as to paint their history to their liking. The Communist Party is very opaque in exposing historical information denying access to serious scholars which limits effective research as archival sources are constantly tampered with to suit Party purposes. At this time when the world is keenly focused on China due to Wuhan Virus and we have added concern over their territorial aggression, it is necessary to recount the basic history of China.

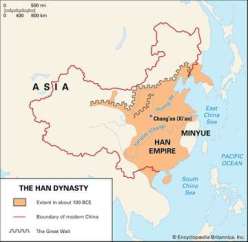

Few will disagree with the fact that Chinese are the oldest living civilisation and its contributions to human progress have been immense. Its history, spread over thousands of years, is too vast to capture over a blogpost. As we are concerned with modern China which emerged exactly in mid twentieth century to influence the entire globe, and to threaten India every now and then, we can try to get over its long history quickly. Chinese history in many ways is the history of Dynasties and could be easier to narrate dynasty wise. Leaving aside the Xia dynasty(2100 to 1600 BC) which is semi mythical the first Chinese dynasty was the Shang(1600 to 1050 BC) that was overthrown by the Zhou(1050 to 256 BC) which disintegrated Into public chaos called the warring states period that ended when the Qin Emperor(221 to 206 BC) was able to extend his Power over most of the heretofore warring states, but the Qin were replaced by the Han(206 BC to 220 AD) which was the dynasty that really set the pattern for China’s history and lasted for almost 400 years after which the country again fell into political chaos out of which rose the Sui(581 to 618 AD) quickly followed by the Tang(618 to 906 AD), who in turn were replaced, after a short period of no dynasty by the Song(960 to 1269 AD) who saw a huge growth in China’s commerce that was still not enough to prevent them from being conquered by the Yuan(1279 to 1368AD), who were both unusual and unpopular because they were Mongols which sparked the rise of the Ming(1368 to 1644 AD), the dynasty that completed building of the Great Wall and created amazing potteries that did not save them falling to the Manchus, who founded the dynasty called the Qing(1644 to 1911 AD) which was the last dynasty because in 1911 there was a rebellion led by Sun Yat Sen that ended the rule of dynasties to establish the Republic of China which had to fight the Japanese colonisers on one front and the newly formed Communists on the other over a prolonged and bloody civil war that ended in 1949 with the victory of the Communists that established Mao’s People’s Republic of China that is staring us in the eye now. Is it bad for a one sentence history of China?

But China is too important to get over in a single sentence. It’s a civilisation that taught humankind to evolve into a complex cultural empire creating its own unique solution to problems of sustaining vast population to an orderly productive society. In its evolution China contributed perhaps maximum important concepts of early technology without which the world couldn’t have made that transition from agrarian to industrial society. These illustratively include something as simple as wheelbarrow to advanced ones like iron and steel smelting, the compass and gun powder to silk, paper making, printing, paper currency, tea, deep drilling, porcelain and organised civil service among many others. It has always been associated with scale with the 5000 miles Great Wall and great canals standing for centuries as signatures. All these achievements are closely aligned to its many dynasty that ruled vast empire over long periods of time.

According to Chinese belief the fall of one dynasty and rise of another happen in accordance with divine intervention. To understand China is to understand its rule by great emperors and its sanction they derived from heaven as codified by Confucian philosophy. The Chinese believe that the rulers receive mandate from heaven by virtue of which they rule the people and they continue to do so as long as they stick to a moral behaviour. Any deviation from this moral behaviour lose them this mandate which then passes on to next dynasty. The Chinese have expanded this mandate to assume that the world is a collective solar system with China as the sun. Hence, every other people and other nation will stick to its assigned position in this system and orbit around China in complete obeisance. This is reinforced by the Confucian notion of harmony where family and society are strictly hierarchical.

In order to understand China it is vital to know Confucius and Confucianism. Confucius (551 to 479 BC) was a minor official in the government during the warring states period. He propounded a social and political system for stable state and society. Though none adopted his system during his lifetime, nevertheless his recipe was ultimately adopted to become the basis for Chinese government, education and general way of life. Confucius argued that the key to bringing about a strong and peaceful State was to look to the past and the model of the sage emperors. By following their example of upright moral behaviour the emperor could bring order to China. His idea of morally upright behaviour boils down to a person knowing his or her place in a series of hierarchical relationships where everyone is either a superior or an inferior. The key relationship in society as per Confucius is that between father and son. The son would respect the father and father would act respectably. This idea applies specifically to the emperor who is like the father to the whole country, something which is retained even now by the Communist Party which has taken over the mantle of the emperor. More of it later when we come to the period of Chinese Communist Party (CPC).

We Indians are highly suspicious of China’s motives and deeply concerned with its meteoric rise since our 1962 defeat. It is, therefore, important to discuss our relationship with China from the beginning so as to find a perspective to the current and the future. China and India share very old history and relationship as from ancient ages they have been centres of spiritual and religious activities. Besides, both share sufferings from western colonialism in modern times. Before European colonisation, China and India enjoyed 33 percent and 25 percent respectively of the world’s manufactured goods. China under the Song (960- 1279) and Qing (1644- 1912) dynasties was the superpower. Under the Guptas (c. 320- c.550 ce) and Mughals (1526- 1857), India’s economic, military, and cultural prowess was an object of envy. However, political contacts between them had been few, may be because of the formidable Himalayas separating them. Culturally, it had been mostly from India to China, with Buddhism being the stand out while Taoism or Confucianism had never made any dent on India. There are famous travellers from China visiting India, namely Fa Xian(Fa Hein) in 399 AD and Xian Zang (Hiuen Tsang) twice in 627 and 643 AD. However, their accounts tell more about ourselves than about China. Some religious and cultural interactions existed between us during the first few centuries AD until the Islamic invasion in India made both countries living as strangers until nineteenth century, when Europeans colonised both. And that is where the root of Chinese grudge against India lies to which we’ll come later.

The Manchus formed Qing dynasty, one of the two non Han dynasty to rule China with the Mongol Yuan dynasty being the other, enjoyed the longest reign of any dynasty from 1644 to 1912 AD. This Qing era saw initial prosperity but soon slides to tumultuous fall to end dynasty rule in China. The down fall of the Qings was caused by over a century of Western humiliation and harassment coming at the heels of ruler incompetence, corruption, peasant unrest, and population growth combined with natural disasters leading to food shortages and famine. Arrogant belief of the Ming dynasty of the superiority of the Chinese to all other countries made China to stop trade with outsiders, a policy retained by the successor Qings. This isolation fatally weakened China’s economy. Meanwhile the rapidly industrialising European powers sought market opening into China. As usual the British having established a strong toehold through East India Company in India took the lead to enter China. Initially the vastness of the country and its huge population ruled by a single Emperor made China look too inscrutable and formidable to penetrate. The British bided their time adopting the same strategy as they did with Mughal Emperors. Into the 19th century, the British having conquered large parts of India became emboldened to venture into China. And greedy too as they expected much more profit from the country which was the source of so much goods that were staple consumption for Europeans since the early days of the Silk Road.

In the early nineteenth century, trade was a common language between China and Britain despite the great differences in their national cultures. Britain had established itself as the premier power of Europe having defeated Napoleon and France. After the passing of the first Reform Bill of 1832, the character of British politics changed as power started flowing out of the landed aristocracy to the newly emerging mercantile Class. British aggressive nationalism was cleverly mixed by the merchants to assert its position in trade with other countries. There was a tradition in China for all visitors to ‘kowtow’ in Court, a ceremony of prostrating before the Emperor, a practice too humiliating for the powerful British. It was seen as the ultimate symbol of Chinese arrogance and inflexibility that became a sort of hindsight logic for the Opium Wars. The clever merchants twisted the reasoning of those wars as the Chinese refusal to treat the Westerners as equal, something that fitted with the Chinese philosophy of the centrality and superiority of their Emperors. However, the reasons of those wars were economic profit rather than national pride.

When first quarter of the 19 th century was coming to an end, the British realised that they had to pay too much in silver to China for the host of goods they bought from them. There was a huge balance of payment issue in those trades as Britain had too little to sell to the Chinese at that point of time. To offset the negative balance they indulged in a concept of ‘carry trade’ where you find stuff from third country to sell to China and utilise the realisation to buy Chinese stuff. What would have been better than to use India as that third country? So they sourced Opium in large quantity from India by establishing a tight monopoly over its cultivation and trade to sell in China as that country had become too addicted during the decadence of Qing period. In less than thirty years between 1810 and 1838 opium imports into China increased from 4500 to 40000 chests. Like all narcotics trade, this led to wide spread illegality as Chinese smugglers entered the market by buying opium in high seas from British and American traders and distributing it illegally in the mainland through their network which resulted in the Qing losing taxes and the stuff getting cheaper by the day to attract increased consumption thereby severely affecting Chinese farming and manufacturing activities. In the middle of the second decade of 19th century the Emperor outlawed smoking of opium imposing punishment of beating offenders 100 times which, however, was not enough to prevent the push factors of opium by the British. When some over zealous Chinese official confiscated and threw opium stock into the water, the newly elected merchant lords demanded the British government to act to safeguard their financial interests. Britain bombarded the port city of Guangzhou defeating the hapless Chinese easily and forced them to sign the treaty of Nanjing in 1844 where by way of settlement China was made to give the British five ports, cede Hong Kong, limit tariffs, grant citizenship rights to British in China and pay the cost of war. Defeat in the second Opium War(1856-60) led to the carving of China like a melon by foreign powers competing for “spheres of influence” on Chinese soil. It thus began what China calls the “Century of Humiliation,” when foreign powers forced weak Chinese governments to cede territory and sign unequal treaties. After the second defeat in 1860 China had to legalise opium and began massive domestic production. By the time 19th century ended opium was no longer the key commodity of trade as China’s domestic production was enough to neutralise imports. But by then Britain was sufficiently industrialised to have lots of goods to sell to the world. China had fallen behind the Europeans in every aspect of manufacturing and trade. Imperial China was completely imperialised by the West.

In course of the second Opium War, Britain and France invaded the capital city of Peking and burnt down the Forbidden Palace, the sacred abode of the Emperor. The Chinese were riled that this attacking force included substantial number of Indian soldiers led by a handful of British and French commanders. Britain seized large tracts of area in the mainland and dominated the city of Shanghai which got indirectly controlled by British administration for some years from Calcutta. Besides, China’s borders were arbitrarily fixed with British India without making any permanent demarcation. These memories served as China’s paranoid scar against India and it didn’t help at all that after both country’s independence, India, particularly its Prime Minister Nehru, hugged plenty of global attention which Mao and his China thought as their due. The feelings against India ingrained in Chinese minds became very apparent to me when I visited the Forbidden Palace the first time. When the tourist guide, the souvenir shop owner and the sellers of artful Chinese paintings tell you about the Indian soldiers’ sacking of the Palace you know that it is a deep scar in Chinese minds. These feelings are carefully nurtured and used by the Communist Party against India in its long term goal of redressing the wounds of history.

(Jena, former principal chief commissioner of Income Tax, will dwell upon the post dynasty history of China and its implications upon world and India in the next part.)